I enjoyed this article by Jeremy Keith on writing alt text for images. In case you’re not aware of what “alt text” or (“alternative” text) is, it’s the text value of the alt attribute of an <img>. It should describe the image (although in practice doesn’t always!).

As a user you might never notice alt text, but there are contexts where it’s incredibly important. Screenreaders will announce the alt attribute to a user, so for someone who is blind or partially sighted, the alt attribute can provide vital content that might otherwise be missed. It’s not good practice to put important text content in an image, but if for some reason you do have to do it then providing the same information in the alt text is essential to ensuring screenreader users get an equivalent experience.

Another time alt text becomes useful is if an image fails to load. This sometimes happens in an email client, or maybe there’s a bad connection. Or maybe the image just takes a really long time to download. In these cases the alt text will be displayed to the user as a placeholder.

As Jeremy points out, writing alt text isn’t always straightforward, and often requires thought, consideration and empathy. That’s why I have a particular loathing for CMSs that default to using the file name as alt text. Imagine, as a screenreader user, being read out file names such as “Screenshot 2022-05-22 at 14-43-16.png”. Unless all content authors are well-trained, this practice is likely to result in some very inaccessible alt text, where in fact, even an empty alt attribute would be preferable.

Empty or missing alt attributes

An empty alt attribute isn’t necessarily a bad thing: Images with alt="" will be interpreted by screenreaders as purely decorative and therefore ignored, which is entirely appropriate for, say, an image uses as a decorative background. It can also be a good idea to use an empty alt attribute when the image is already described by the surrounding text. (The W3C page on decorative images includes some useful examples.) But it shouldn’t be used as a lazy shortcut to skip the work of writing helpful alt text.

There’s an important difference between an empty alt attribute and one that’s missing entirely. A screenreader coming across an image with a missing alt attribute will announce the file name instead, which, as we've seen, is usually unhelpful.

Writing alt text for text-heavy images

An issue I’ve seen come up increasingly frequently is writing alt text for images that contain a lot of text. It’s become common to see people post screenshots of text on Twitter: displaying interactions when you don’t want to amplify the original author by retweeting or quote-tweeting, or posting a long conversation that has occurred via another medium are a couple of use cases.

Another case (popular in the developer community) is sharing code examples. Sites like Carbon allow you to “prettify” your code examples and save them as images to share on social media. Without alt text these code examples are meaningless to users without the means to physically see the images.

Happily, Twitter now allows users to provide alt text for images, so in many cases including the code as text should suffice. But for longer text, what should we do? One possibility is to provide a link to the original content in the tweet itself. In the case of code, or even long-form content when it can’t be accessed elsewhere, it could be a Github Gist, for example. (I’ve seen Dave Darnes do this.)

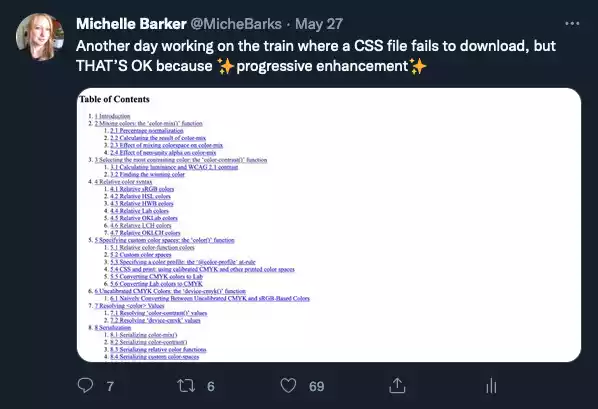

I had a bit of an unusual case that gave me pause for thought recently when I posted a screenshot of an HTML webpage that had loaded without its CSS file. It contained a lot of text, but the point of posting the image was to show what that page looked like without its CSS, not the text itself.

I opted for alt text that described the content of the image, rather than copy-pasting the entire text:

Screenshot of W3C CSS Color Module spec page showing table of contents

My alt text was probably a little rushed and imperfect. I probably should have included the fact that the webpage was displayed in its pure HTML, unstyled form. But hopefully would have given enough information for someone to get the gist of the image, especially when accompanied by the original tweet. As Jeremy says in his article, the more you write it, the better you get.