I’ve just come back from State of the Browser, a wonderful, community-run conference in London, where I gave a talk about debugging CSS Grid. The conference intentionally focused on web standards, rather than the latest tooling or frameworks. Each of the speakers had their own area of expertise, but what was especially successful was the way the talks were, whether by accident or design, woven seemlessly together by a common thread: making the web work for everyone. Bruce Lawson set the tone early on by quoting Sir Tim Berners Lee (or “Uncle Timbo”, as Bruce would have him known):

This is for everyone.

It has certainly struck me (and no doubt many others) in recent times that the value of a front end developer seems to be the JavaScript they can write and the fancy frameworks they can use, leaving web fundamentals like CSS, HTML and accessibility worryingly undervalued. Whole swathes of the web are entirely inaccessible to many people with any kind of impairment, in developing countries, or without access to the latest device or a fast connection. We haven’t truly built a web for everyone.

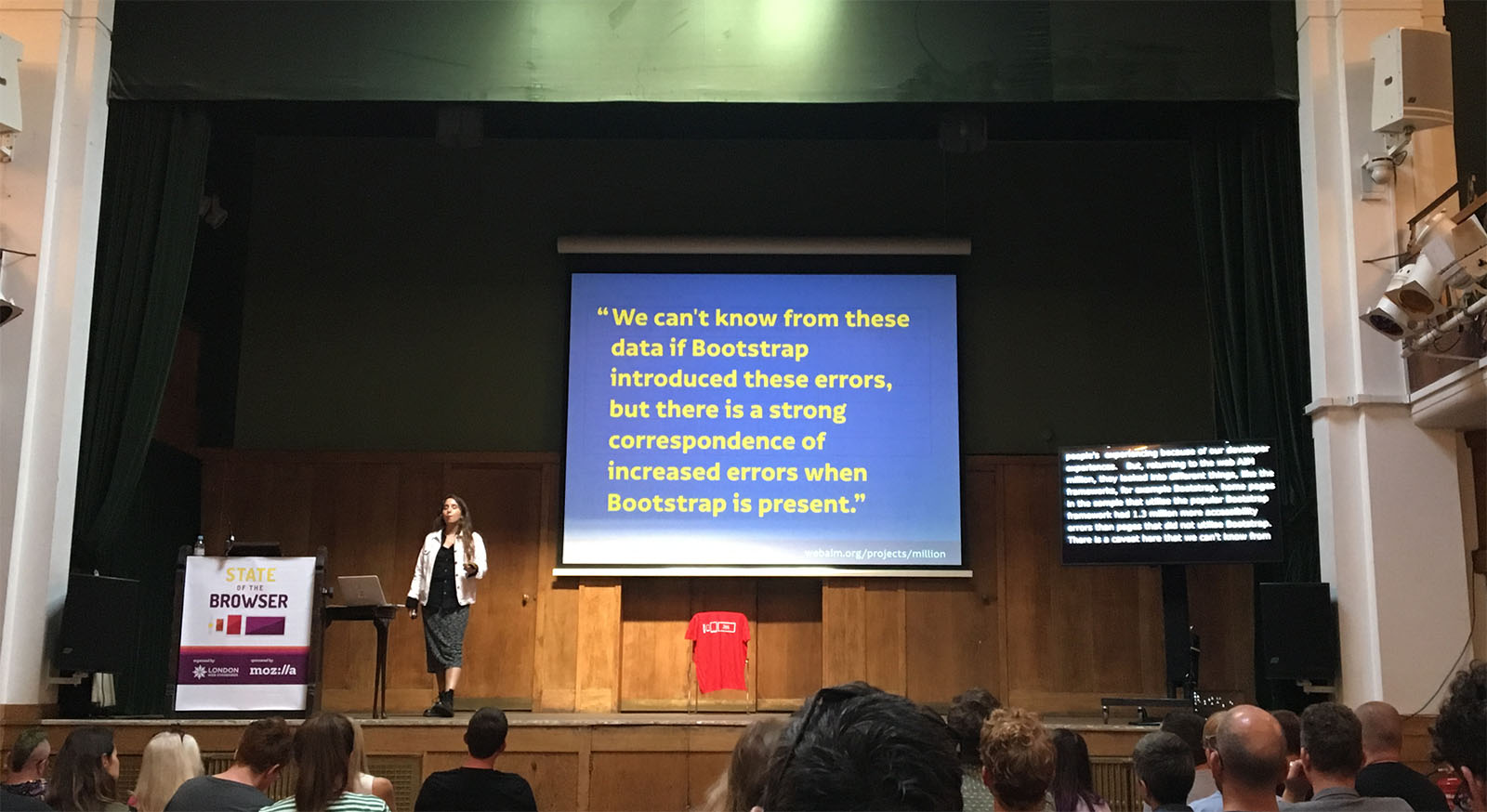

It would be difficult to single out any particular talk from State of the Browser as a highlight, as the standard was so high across the board. HTML, accessibility, performance and CSS were all covered. What was particularly notable was that JavaScript was barely mentioned, except with a warning to use it sparingly. This might feel old-fashioned, but in fact it emphasised how little JavaScript is actually vital to the user experience, and how important it is to invest in the skills that make the web useable for everyone. Often, we’re sacrificing accessibility for the sake of a slick experience for the minority or, even worse, for the sake of developer experience. Laura Kalbag pointed out in her talk that there is a correlation between use of frameworks and higher instances of accessibility errors. There could be many different reasons for that – it doesn’t necessarily follow that frameworks cause the errors – but when the emphasis is on learning a framework, rather than fully understanding the fundamentals, then it certainly seems logical that accessibility suffers as a result.

Mostly, JavaScript is an enhancement, and yet often it’s a skill prized above all else to companies looking to hire developers. Most job adverts these days highlight JavaScript as the number one must-have, with HTML and CSS thrown in for good measure (if at all), as if they can be picked up in an afternoon, and don’t require years of practical experience and careful consideration to do well. Accessibility is a large and complex area, yet it’s treated as an afterthought, with the people who specialise in it hugely undervalued.

I’d like to think that conferences like State of the Browser are symptomatic of a renewed industry-wide focus on web fundamentals. But part of me fears this isn’t the case, and that it further demonstrates the divide between framework-focused developers and those concerned with the web’s founding principles.

There doesn’t need to be this divide.

I would never discourage someone entering the industry from learning a JS framework because, for better or worse, it’s a skill that might get you a job. It’s all very well for established and well-connected people in the industry to denigrate frameworks, but there’s no getting around the fact that companies do want those skills. I worry that some well-meaning advice could cause newer developers to exclude themselves from the talent pool by eschewing frameworks, and never get onto the career ladder. But above anything else, State of the Browser reminded me how necessary it is to keep banging the drum for a better and more inclusive web, as we can’t afford to let the message get lost. I hope the developers entering this brave new JavaScript world attend conferences like this, listen to the advice, and in turn become advocates of a web for everyone.

Further reading

This article by Bryan Robinson is worth reading: What the Rule of Least Power means for modern developers. It refers to The Rule of Least Power, a principle drawn up by Sir Tim Berners-Lee and Noah Mendelsohn, which recommends choosing the least powerful language for a given purpose – also referenced in Bruce Lawson’s talk.